Mapping Africa's Green Mineral Partnerships: A Q&A Discussion with Judy Hofmeyr of the African Policy Research Institute

Posted on 13 June 2025

A policy paper published by the African Policy Research Institute maps critical mineral agreements between African countries and foreign actors with the aim of providing greater transparency and accountability in the policy landscape.

Executive Summary

- The African Policy Research Institute (APRI) has mapped nearly 100 mineral agreements between African states and international partners, offering the most comprehensive public record of such deals to date.

- The study highlights how the scramble for critical minerals – such as cobalt, lithium and rare earth minerals – is re-shaping geopolitics and drawing Africa into the centre of the energy transition.

- Findings reveal an uneven landscape: rising state-to-state agreements, lack of transparency and risks of inequitable outcomes for African communities.

- Despite promises of local value addition, many agreements remain vague, underfunded or misaligned with continental goals.

- APRI argues that greater focus on transparency, shared learning and continental solidarity are essential for Africa to negotiate fairer, development-driven mineral partnerships.

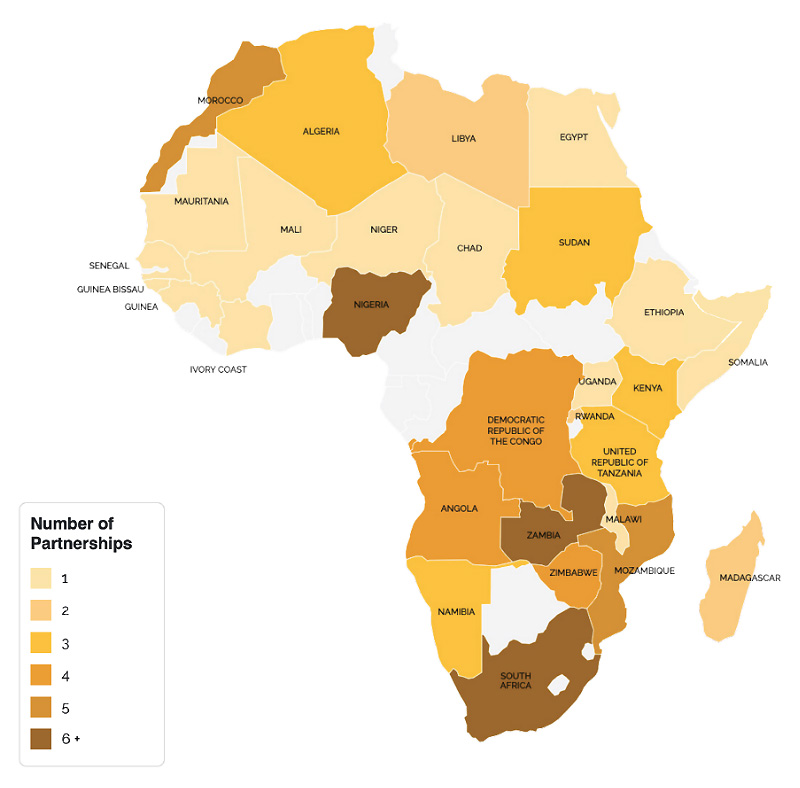

In 2024, the Africa Policy Research Institute’s (APRI) Geopolitics and Geoeconomics team launched a study to map and analyse emerging mineral agreements between African states and international partners, amid growing global demand for critical minerals essential to the energy transition. The project produced both an interactive map and a detailed report, offering a comprehensive overview of nearly a hundred mineral-related partnerships across the continent. These include bilateral and multilateral agreements focused on securing access to resources such as lithium, cobalt, manganese, and rare earth elements.

Mapping Africa’s Green Mineral Partnerships (Report)

The database of agreements was compiled through an extensive online search, drawing on government publications, media reports, and open-source platforms. While not exhaustive, the collection represents the most publicly available and searchable record of such agreements to date. The accompanying report examines 12 selected agreements in greater depth, assessing their structure, objectives, and implications. Together, these resources offer a valuable foundation for further research, policy debate, and public scrutiny.

The questions that follow reflect on the origins and main findings of the project and are intended to support a broader conversation about how Africa’s mineral partnerships are being shaped in this new era. The questions were posed to Judy Hofmeyr, Green Transition Minerals Fellow at the African Policy Research Institute – one of the co-authors of the mapping report. This report, alongside many other policy resources such as mineral profiles, news and strategies, can be found on the African Green Minerals Observatory website.

What was the rationale for the African Policy Research Institute to conduct this research on mapping Africa’s green mineral partnerships?

Our main motivation was to enable both a comprehensive and a comparative view of critical mineral agreements in Africa. At the most basic level, we wanted to bring greater transparency to a complex and fragmented landscape that, until now, has not been made publicly accessible in this way. But the reason we believe this kind of transparency matters is because African states have, on the whole, not had a strong track record when it comes to foreign involvement in their minerals sector. It is stating the obvious to say that these deals have rarely delivered the kinds of developmental returns they should have. As SAIIA’s work has shown, the governance of minerals across much of the continent in recent decades has significantly undermined states’ ability to exercise mineral and energy sovereignty.

With that history in mind, the current rush for access to energy transition or ‘critical’ minerals has brought renewed attention from foreign governments. Africa sits at the centre of rising global demand for critical minerals such as lithium, graphite, cobalt, coltan, manganese, platinum, tantalum, and bauxite; minerals that are essential to a wide range of modern technologies, from electric vehicles and mobile phones to medical devices and renewable energy infrastructure.

These minerals are increasingly central to geopolitics. This is because (a) most supply chains remain concentrated in China, (b) critical minerals are directly tied to national energy and security strategies, and (c) countries are eager to stay competitive in a fast-growing green tech market. And let’s not forget the small matter of (d) having to address the impending climate crisis. These dynamics have spurred a wave of critical mineral strategies worldwide, most of them geared towards securing access to raw materials and increasing processing capacity domestically. As a result, considerable pressure on upstream supply is expected. Battery demand alone will require over 300 new mines by 2035, and many of these are expected to be in Africa.

We are seeing this active, realpolitik pursuit play out in the rise in mineral agreements with African states. Of the agreements we were able to identify in our research, 42% were drafted in the last five years. In some circles, there is a cautious sense of optimism that this renewed interest presents a ‘window of opportunity’. With growing global competition and stronger local capabilities, some African states may now be better positioned to negotiate more favourable terms. It is therefore vital that Africa’s mineral diplomacy is made visible and open to scrutiny. This is essential from a democratic perspective – not only to hold governments accountable for the deals they sign, but also to understand whether these arrangements are ushering in a new era of mineral governance or repeating old patterns under a new name.

What were some of the key findings with regard to the nature of these mineral agreements and the evolving dynamics of minerals diplomacy in Africa?

The first relates to the actors involved. Our analysis highlights the prominence of countries such as China and Russia, while agreements with more established mining powers like Australia and Canada appear far less frequently. This may reflect the perception that African countries present greater risk, or it may be that companies from these countries already have a strong commercial presence, reducing the need for formal state-to-state agreements. It is also worth noting the diversity of international actors engaging with African states. Our map features 24 bilateral partners of African countries – such as the US, the EU, China – but also India, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Brazil, amongst many others.

An additional reflection is that, in this era of critical mineral pursuit, the unit of analysis for policy, research, and advocacy work has shifted back to the state. Multinational corporations have for long been on the forefront of shaping extractive regimes – and of course they continue to be – but there is now a clear increase in the interest and involvement of states, both within Africa and internationally.

A second finding concerns the content and structure of the agreements, which vary considerably in form and emphasis. Some prioritise direct government cooperation and the use of public funds, while others focus on improving the investment climate for private sector actors, which may take longer to yield tangible results. Some agreements include explicit social and environmental safeguards, while others make no mention of these issues. In our view, these differences reflect broader political, historical, and economic considerations, with countries selecting partners and determining terms based on strategic trade relations, shared histories, or broader diplomatic and commercial interests.

It is promising to see that most agreements acknowledge – at least in principle – Africa’s now commonly known goals for local processing and value addition. This suggests that such priorities are being brought into negotiation spaces and are gaining recognition from foreign partners.

However, there are several reasons to remain cautious. First, it remains uncertain whether these memoranda will result in concrete outcomes. One of the main challenges is whether they can attract the scale of investment required to meet their goals, especially from private investors and development finance institutions. This question is particularly relevant in the context of fiscal constraints, and because building robust value chains requires more than tax revenue from resource extraction.

Even when funds are committed, there is no guarantee they will contribute to developing the technical or industrial capabilities that enable upstream and downstream sectors. Reliable infrastructure, energy, and logistics are also essential for value addition, and it is unclear whether these support sectors are receiving sufficient attention. There is also a risk that current commitments are broad and unfocused. To be effective, support for value addition needs to be directed toward specific, viable projects that have the potential to become regionally or globally competitive.

Another important consideration is how these agreements affect regional cooperation, which is crucial for Africa’s developmental goals. Value addition at the scale the continent needs will only be achievable through cross-border coordination, shared infrastructure, and access to regional markets. It is unclear whether bilateral relations with non-African states will support or undermine the ability of African countries to work together in this respect.

Finally, there is growing concern about how these agreements will affect communities near mining sites. There is a real risk that populations living near sites of critical mineral extraction who are most likely to bear the brunt of mining harms may be “crushed under the weight of a grand green narrative”. The social and environmental costs of accelerated extraction need to be properly considered, and the rights and interests of affected people must not be overlooked. However, this is very hard to do in practice, since sustainability considerations are seen to slow projects down.

The research highlights the limited transparency and public accessibility of many of these mineral agreements. Why is this a concerning finding and how can mapping exercises such as this help in addressing this problem?

The opacity of these agreements is concerning because it weakens accountability, public oversight, and informed participation in decision-making. These principles are essential to a broader understanding of development – one that values civic freedoms and democratic governance, not just high-level economic indicators.

Secondly, where these agreements are followed by tangible commitments of capital, they have far-reaching material consequences. They can and will shape how benefits are shared, how harms are managed, and whether long-term development goals are advanced.

When negotiations and terms are hidden from public view, it becomes difficult for civil society, communities, and even parliaments to assess whether these deals serve the public interest. Mapping exercises like this one provide a baseline for further scrutiny and comparison, enabling stakeholders to spot patterns, identify gaps, and advocate for better governance.

While the report focuses on external actors, it stresses that “African countries are not passive participants in these partnerships.” How do you believe research of this kind can help strengthen African agency when it comes to negotiating state-to-state mineral agreements?

Information asymmetry has been a major driver of Africa’s persistent unfavourable terms of extraction. Negotiating strong mineral agreements requires deep strategic, legal, financial, and geological expertise, yet many African governments often face resource constraints when engaging with foreign counterparts who bring in highly experienced negotiation teams. Research of this kind can play a vital role by helping to close persistent information gaps about governance decisions and outcomes on the continent. This can help policymakers, regional bodies, and advisors to better understand what has been agreed elsewhere, learn from outcomes, and consequently, build stronger negotiating positions.

Moreover, by highlighting patterns and common challenges, our hope is that this type of research can support greater solidarity among African states. Transparency across borders allows governments to better understand how their peers are approaching similar negotiations, helping to avoid situations where countries are played off against one another. This is especially important in a context where competition for foreign investment often results in a “race to the bottom,” with states making increasingly generous concessions to attract partners. Regional cooperation – through shared standards, coordinated negotiation positions, or collective investment frameworks – can help to counter these dynamics.

If there is one key insight you learnt from conducting the research that you would like for policymakers to pay attention to, what is this insight and why do you believe it is important?

One key insight we hope policymakers take seriously is the importance of greater continental solidarity in minerals diplomacy. We recognise the complexity of aligning diverse national interests, but there is a strong foundation to build on. The African Green Minerals Strategy offers a clear, homegrown blueprint that can guide more unified engagement with international partners.

Equally important is the need to ensure that ordinary Africans are not left behind. The pace and momentum of critical minerals investment is encouraging, but it cannot come at the expense of human rights. Conversations about value addition and those about social impact cannot continue to take place in isolation from one another. Communities and workers must be treated as central actors, not afterthoughts. Our greatest challenge therefore will be integrating justice into the heart of economic policy.